Since low-code became the new buzzword, I wondered whether there was anything really different in the low-code movement compared to what we used to call model-driven engineering/development. The 1st Low-code workshop (part of the Models 2020 conference) was the perfect excuse to take some time to reflect and write down my thoughts on this topic.

What you can read next (you can also download the pdf version), it is the result of my thinking sessions. Also embedded the slides of the talk I prepared to present the paper (see at the bottom). Both include some of the feedback I got when publishing the first version of this post (thanks to all for the great feedback you gave me!). I do believe this (the positioning of low-code in the model-driven world) is a discussion we need to keep having as a community. Even if we don’t reach any consensus.

DISCLAIMERS: 1 – This is a short position paper and should be read and interpreted as such. 2 – It is probably controversial. If you feel offended when reading it, I did a good job. I think the point of position papers is making strong and bold statements that help to start a discussion. 3 – It is difficult to “scientifically” compare two terms when one of them (“low-code”) is not scientifically defined but needs to be inferred from studying the set of tools that call themselves as such.

Having said this, keep reading for my thoughts regarding the positioning of the low-code movement within the field of model-driven engineering. In particular, I try to give some partial answers to the questions

- Is there something fundamentally new behind the low-code movement?

- How does it relate to other concepts like Model-Driven Engineering or Model-Driven development?

- what are the implications for researchers in the modeling community?.

Introduction

Low-code application platforms accelerate app delivery by dramatically reducing the amount of hand-coding required (definition is taken from this Forrester report [5], attributed as the origin of the term low-code). This is clearly not the first time the software engineering community attempts to reduce manual coding by combining visual development techniques (what we would call “models”) and code generation. In fact, as Grady Booch says, the entire history of software engineering is about raising the level of abstraction.

Low-code is the latest attempt to reduce the amount of manual coding required to develop a software application. This is the same goal we have been chasing since the beginning of software engineering Click To TweetLow-code can be traced back to model-driven engineering. But model-driven engineering itself can be traced back to CASE (Computer-Aided Software Engineering) tools. Already in 1991, in the 1st edition of the well-known CAiSE conference, we could find papers stating concepts like: “Given the final model, the complete computerized information system can be automatically generated”[2] or “we arrive at a specification from which executable code can be automatically generated”[4].

At the same time, the impact of low-code in the business world is also evident nowadays, including some bold projections but also actual factual numbers regarding recent investments in low-code tools, the commercial success of some of them or just the fact that all the largest software companies are making sure they have some kind of offering in this domain.

Low-Code vs Model-Driven vs Model-Based vs No-code

We do not have universal definitions for all the MD* concepts. My own (informal) definitions are the following:

- Model-driven engineering (MDE): any software engineering process where models have a fundamental role and drive the engineering tasks.

- Model-driven development (MDD): MDE applied to forward engineering, i.e. model-driven for software development.

- MDA is the OMG’s particular vision of MDD and thus relies on the use of OMG standards.

- Model-based engineering/development: Softer version of the previous respective concepts. In a MBE process, software models play an important role although they are not neces-sarily the key artifacts of the engineering/development (i.e. they do NOT “drive” the process).

An example of the MBE vs MDE difference would be a development process where, in the analysis phase, designers specify the platform-independent models of the system but then these models are directly handed out to the programmers to manually write the code (no automatic code-generation involved and no explicit definition of any platform-specific model). In this process, models still play an important role but are not the basis of the development process.

Based on the above definitions, I see low-code as a synonym of model-driven development. If anything, we could see low-code as a more restrictive view of MDD where we target only a concrete type of software applications: data-intensive web/mobile apps.

Note that the term no-code is sometimes used as a slight variation of low-code. In fact, we can often see tools defining themselves as no-code/low-code tools. Nevertheless, to me, the key characteristic of a no-code approach is that app designers should write zero code to create and deploy the application. This limits a lot what you can actually do with no-code tools. We are basically looking at template-based frameworks or creation of workflows mixing predefined connectors to external applications where the designers, at most, decide when and how certain actions should be triggered

Another way to compare these different paradigms is by looking at how much manual code you are expected to write. In MBE, you may have to write all the code. Instead, in MDD and low-code, most of the code should be generated but you still may need to customize and complete the generated code (most MDD tools include some kind of black box modeling primitive where you can write any custom code that should be added during the generation process). In no-code you should write zero code.

Obviously, more research is needed to evaluate the low-code tools in the market and better characterize them in less coarse-grained categories than those presented here. In fact, right now, there is basically no research around the low-code movement (a quick search only reveals some papers about tools that classify themselves as low-code but not about low-code itself as the object of study), something that I am sure this workshop will start to change.

Low-code is trending

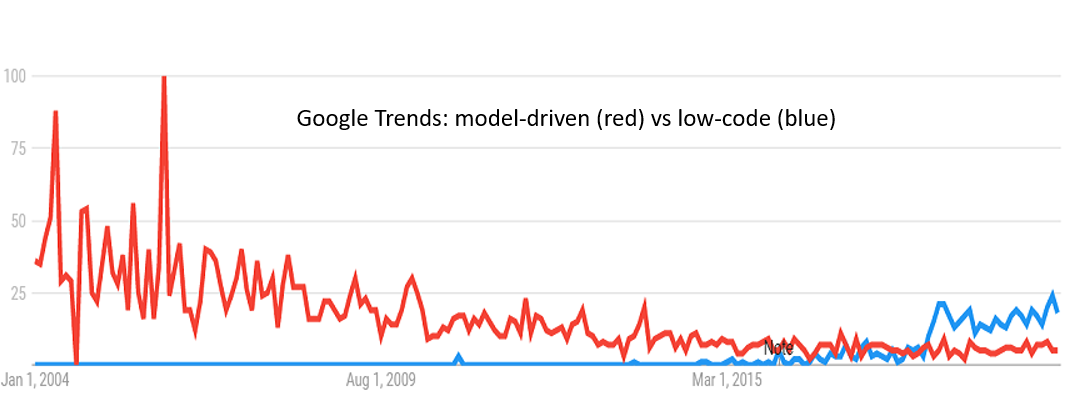

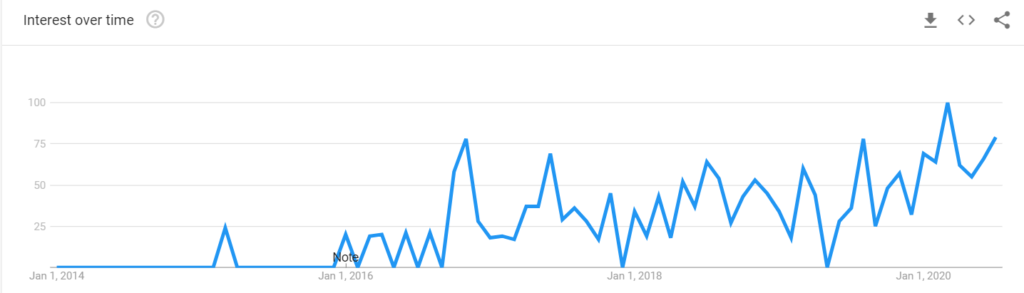

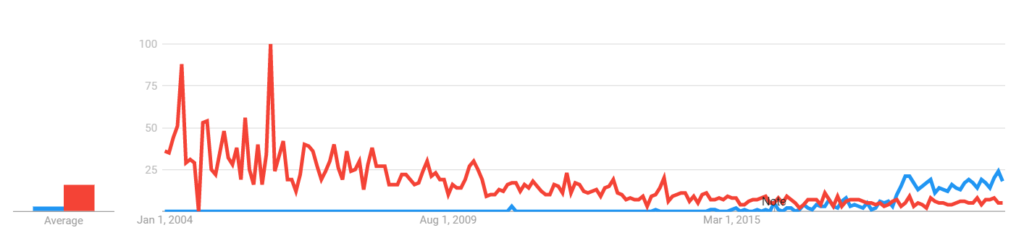

As shown in the Figure 1, interest in low-code is as its peak, even if, as depicted in Figure 2, this peak is much smaller than the attention model-driven was getting on its prime.

Google Trends graphic showing the search interest for the low-code term

But, if, technically speaking, low-code does not really bring anything new to the table, why this popularity?.

- First of all, I think low-code conveys a much clearer message than model-driven/model-based. Model is a much ambiguous word and therefore the concept of model-driven is more difficult to explain than low-code (everybody has a clear view of what code is, and low-code becomes self-explanatory).

- Secondly, we know modeling scares developers away. Instead, low-code sounds more familiar. It is the same they already do (coding) but less of it.

- Moreover, the application scenarios for low-code are also clearer. Instead of selling that you can do anything with MDD (which ends up generating mistrust), low-code looks more credible by targeting specific types of applications, those that are most needed in industry.

- Low-code is also typically a one-shot modeling approach, meaning that you have models and the generated code, no complex chains of refinement, no model transformations, no nothing.

- And on average, low-code tools are nicer than our traditional heavy modeling tools. For instance, most are web-based and do not depend on EMF.

All in all, I haven’t seen any notation, concept, model type or generation technique in a low-code tool that I couldn’t find similarly in the model-driven world. But for sure, these same techniques are presented, configured, adapted and “sold” differently, which in the end makes a big difference in how low-code novelty and usefulness are perceived. And the success of a MDE project often depends more on social and managerial aspects than on purely technical ones [3]. This does not come for free (lack of interoperability, vendor lock-in, expensive business models,..) but this does not seem to deter the community at the moment.

Adam Grant explains this need of presenting an innovation in a way that it’s more familiar to the target market in his Originals – How Non-conformists move the world:

To succeed, originals must often become tempered radicals. They believe in values that depart from traditions and ideas that go against the grain, yet they learn to tone down their radicalism by presenting their beliefs and ideas in a ways that are less shocking and more appealing to mainstream audiences

We (the core “MDE” people) were probably too radicals presenting our ideas. The low-code movement understood better how to be tempered radicals!

Low-code as an opportunity

As pointed out before, I do not believe there is any fundamental technical difference between MDD and the low-code trend. In fact, we could take almost any of the open challenges in model-driven engineering [1] and just change “model-driven” by “low-code” to get, for free, a research roadmap for low-code development (e.g. we need better ways to integrate AI in low-code tools or we should strive as a community to build a shared repository of low-code examples for future research).

But I do not see this as being negative. More the opposite. Clearly, low-code is attracting lots of attention, including from people that were never part of the modeling world. In this sense, low-code is lowering the barrier to enter the modeling technical space. As such, to me, low-code is a huge opportunity to bring modeling (and our modeling expertise) to new domains and communities. If we can get more funding/exposure/users/feedback by rebranding ourselves as low-code experts, I am all for it. This is exactly the approach that many well-known so-called low-code companies have taken (feel free to play with the Internet Wayback Machine and see how their websites mutate from visual modeling, agile development, CASE tools and similar keywords to low-code in the last years). Let’s also take this opportunity to better understand the factors that make modeling-like techniques resonate in the broad software community and learn from it.

Low-code is a huge opportunity to bring modeling (and our modeling expertise) to new domains and communities Click To TweetAnd while we do that, let’s keep an eye on the market trends to come. Some low-code vendors are shifting (yet again) their marketing efforts. It may not be long before we start chanting: Low-code is dead, long live multi-experience development.

Slides comparing low-code vs model-driven engineering

References

- Antonio Bucchiarone, Jordi Cabot, Richard F. Paige, and Alfonso Pierantonio. Grand challenges in model-driven engineering: an analysis of the state of the research. Software and Systems Modeling 19, 1 (2020), 5–13. https://doi.org/10. 1007/s10270-019-00773-6

- Jon Atle Gulla, Odd Ivar Lindland, and Geir Willumsen. 1991. PPP: A Integrated CASE Environment. In Advanced Information Systems Engineering, CAiSE’91, Trondheim, Norway, May 13-15, 1991, Proceedings (Lecture Notes in Computer Science, Vol. 498). Springer, 194–221. https://doi.org/10.1007/3-540-54059-8_86

- John Edward Hutchinson, Jon Whittle, and Mark Rouncefield. 2014. Model-driven engineering practices in industry: Social, organizational and managerial factors that lead to success or failure. Sci. Comput. Program. 89 (2014), 144–161. https: //doi.org/10.1016/j.scico.2013.03.017

- John Krogstie, Peter McBrien, Richard Owens, and Anne Helga Seltveit. 1991. Information Systems Development Using a Combination of Process and Rule Based Approaches. In Advanced Information Systems Engineering, CAiSE’91, Trondheim, Norway, May 13-15, 1991, Proceedings (Lecture Notes in Computer Science, Vol. 498). Springer, 319–335. https://doi.org/10.1007/3-540-54059-8_92

- Clay Richardson and John R Rymer. 2014. New Development Platforms Emerge For Customer-Facing Applications. Forrester: Cambridge, MA, USA (2014).

FNR Pearl Chair. Head of the Software Engineering RDI Unit at LIST. Affiliate Professor at University of Luxembourg. More about me.

It’s my impression and experience that a big difference between “outfits” (companies, organisations) that do low/no-code and outfits that do “traditional” MDD is that the former have no idea about software language engineering. Not only do they know little about the field, they’re usually not even aware of the existence of the field. That’s quite likely a disadvantage on the whole, although lack of knowledge could in part also mean “lack of unnecessary luggage”.

This means, at the very least, that we have an opportunity to do a lot of mission work among those outfits. One very concrete opportunity is this one: https://bryter.io/careers/software-language-engineer-m-f-d/ – this is an interesting startup whose CTO is aware of the existence of the field of software language engineering, and convinced of the necessity of hiring for that.

I tend to agree with you. Low-code sells simplicity in the process. But users may not be aware of the “price” of this simplicity (e.g. in terms of the type of applications you can build). If this is what you need then great but otherwise, adaptation is very challenging

the last sentence sums it all up. It’s all about trend now.

Thanks Jordi for a great topic for discussion on many levels, and some very good points. Obviously, low-code is a marketing term, and fills a need for marketing something ‘new’ – MDD etc. aren’t news anymore. As a marketing term it’s clearer, in that it says just one thing in one way (not MBSE, MDA, MDD, MDE etc.). It’s less clear though in what it means: all it says is that code is reduced, but not what the remaining part of the task is replaced with.

I think the biggest distinguishing questions for low-code are:

– what language or format is used for the remaining part of the task;

– is that language and resulting behaviour a fixed black box, customizable or open;

– is the resulting behaviour by interpretation or generation.

The low-code tools and stories I’ve seen tend to focus more on a fixed, closed, proprietary language (often a combination of form-based and simple graphical); often interpreting rather than generating; smallish systems, and greenfield development – often by companies without in-house experience to code those systems from scratch.

In those respects, low-code looks more like the successor of 4GLs. CASE tools and UML-based MD* differed in having an ostensibly standard language, and visibly generating code. Domain-Specific Modeling differs in freedom to define the language and generation / interpretation, so benefits more from in-house know-how, scales better, and integrates better if there is existing hand-made legacy code.

So far, I don’t recall coming across a case where a prospective customer pitted low-code against Domain-Specific Modeling. I think they self-select – if they’re not experienced in coding for their domain, they probably go for low-code, if one exists for that domain and implementation platform. For other domains, some come to us and we built the language in cooperation with them. More experienced coders tend to find fixed low-code solutions frustrating, and build their own DSM solution with MetaEdit+. (And one level higher, we have also seen some low-code tools turning to us, replacing their initial tooling with MetaEdit+.)

I like this idea of seeing low-code as a “fixed-language MDD solution”, also suggested by Hallvard Trætteberg in Twitter.

I agree Low-Code can be seen as a ‘fixed language MDD solution’.

But the language can still be very generic – see Mendix and Outsystems. I would claim that their approaches cover 80% of all ‘administrative’ IT systems (these include our ”classical/boring” Analysis & Design assignments: hotel-booking, library-system, ….

Personally, I think the other aspect of their (Mendix & Outsystems) systems is their highly automated deployment-chain.

While one could say this is not part of the language per-se, it certainly is part of their selling-points & business advantadges.

And then one could wonder whether ‘fixed languages’ could also work in ’embedded systems’

Steven surmises that low-code platforms tend to get self-selected, and in my experience that’s exactly what happens. Customers of Mendix and such just need to find a way to make “traditional” software, without them needing all of the skills of full-stack software developers, or in the same amount. Basically, they need to upgrade from Excel/Access-type home-grown solutions, but haven’t got enough coders to do it with a typical JS/Java, etc. solution. With a low-code solution, they can do 95% with the low-code platform, and coding the remaining 5% through some JS+Java is then not so bad anymore.

Usually, their domain is either nog big enough to warrant implementing a DSL-based approach, or they’re simply even less familiar with the existence of such an approach than a regular software developer.

I can mostly agree with your statements, Jordi. But I do sense a distinction in low-code versus modeling or domain-specific languages, simply by the choice of term. In ‘low-code’, it seems that the part that is not code is not considered an “encoding” but perhaps more of a configuration or set-up. In modeling and DSLs there is more of a recognition that even the ‘not code’ part is, in a sense, a language (and an encoding).

“low code” sounds efficient (low) and focussed on aimed at creating ‘code’. So it an efficient sales message to executives and decision makers. It is much more self explaining than ‘model driven development’, which can only appeal to a more technical community. I think that might explain the growth in search.

Modeling has much broader applications than code in my view. Not all useful models aim to capture aspects of a system that are best represented in software code. For example, in a medical device context, the risk management measures can be captured in a ‘bowtie’ model and partially, but not fully allocated to the software system requirements.

If your framing is ‘code’, you also might miss on other benefits of the higher level abstraction framing that ‘modeling’ brings. As another example, at Philips we used models for interface specifications to consisely capture the interaction between components (See

https://bits-chips.nl/artikel/improving-interface-specifications-with-comma ). Because the interfaces are regard ‘models’, we can also apply model checking.

As Jordi said, i agree that low-code is a more restrictive view of MDD which target only a concrete type of software applications: data-intensive web/mobile apps.

When chosing a low code vendor, there is a risk of vendor lock-in for those vendors that use propriatory model formats . Creating software is expensive, but the life cycle cost of maintining are often much higher. Depending on how long you need to maintain your software stack in the market, capturing a companies domain knowledge in your own DSL might be the better route.

Indeed, modeling goes much beyond than code-generation (this is a distinction I make in the paper regarding how MDE differs from MDD).

And thanks for the pointer to Comma. I didn’t know it (and of course, if you’re open to write a guest blog post introducing it to my readers I’ll be glad to publish it!)

Just a small note. The first CAiSE conference was 1989 and still used the acronym CASE. It is available a a re-publication at http://ceur-ws.org/Vol-961/

Thanks for the clarification. I was not aware of this!

“everybody has a clear view of what code is”

Given that there’s now tens of thousands of “third-generation” programming languages, I’m not really sure that your statement is true.

Buzz words appeal to those chasing silver bullets. In absence of common measurements, the new thing is never known to be better than the old thing. Capers Jones’ spreadsheets are the closest we can come to good comparison, and even those lack a certain amount of discipline in development method definition.

This twitter exchange is also relevant https://twitter.com/JohanDenHaan/status/1306166848862531584

Questioning “code” you must first define what code is.

https://blog.mdriven.net/un-learn-how-to-code-2/

We have always described ourselves as Model Driven – as we took up the baton where Borland and Embarcadero left it with ECO.

But now we describe ourselves as low code or no code – since it reaches the audience better: https://blog.mdriven.net/is-mdriven-really-no-code/

Same for many other vendors, if you spend some time on the Internet Wayback machine you can see the “naming” evolution (e.g. some were calling themselves “agile” when agile was a thing 🙂 )

In my opinion, vendor-locking and lack of focus on operational concerns are mayor issues with these solutions to date.

From my perspective, a successful solution would need to be able to play well with existing source version control systems, ease extensibility through common-used languages and CI/CD workflows on the development side of things. On the operational side, they would need to promote performance, monitoring and resiliency mechanisms as first-class citizens by exposing those concerns to designers. Designers need to be exposed to what the expected performance and availability characteristics the system needs to fulfill. The platform then adjust based on these expectations.

Abstractions tend to work well as long as the system has no performance or resources constraints.

“Abstractions tend to work well as long as the system has no performance or resources constraints.”

I completely disagree. Abstraction is the device that enables assembly code to be used to produce machine code instructions. At a higher abstraction level, C code can be used to produce machine instructions. At an even higher abstraction level, models can be used to produce machine instructions. With adequate compiler technology, none of this abstraction has to affect performance or use more resources.

“Abstraction” is not necessarily equivalent to layers of code calling other layers of code as is often seen being done in many popular object-oriented programming languages.

Agree: abstraction is the act of giving specific, precise things a name (free after Edsger W. Dijkstra). It can often even help with performance, because being able to conveniently phrase your problem in terms of well-chosen abstractions can help you optimise the solution much better than implementing a solution directly using lower-level abstractions

I get that and I am aware that sometimes abstractions can enable mechanisms that may offer performance benefits by the ability of getting more information on the context code runs on. In those situations we see some JIT languages like Java performing better than compiled languages like C++.

However, I see over and over again how projects that were initially implemented in higher abstraction level languages/libraries, having to being re-implemented fully or partially in lower level languages once they hit performance ceilings.

That is an empirical fact that shows how historically we haven’t been good at making abstractions without performance impacts or where the system is designed with accurate performance expectations. It is just that we’ve had more compute power available to compensate (ie: electron apps, I am looking at you 🙂 )

Also, wen you need to do this migration between “coded languages” you can argue that your devs could adapt. How would that be with a set of model designers that are not used at all to code? The impact on human resources, processes and tooling is much bigger in that scenario.

Very true for higher abstraction third generation languages. When you hit performance problems, you start by identifying the slow parts, using a better algorithm where possible or recoding to be faster (and uglier). If that’s not enough, you may replace that part with assembler or a lower-abstraction 3GL.

But for a modeling language with code generation, you have another possibility: rather than changing the model, or replacing that part with code, you can improve the generator. That’s equivalent to improving the compiler, which would be very rare for a project using a 3GL.

Particularly with a domain-specific language, optimizing through generator improvements is easy: the improvement doesn’t need to be good for every possible company and use case, but just this narrow domain and company.

Absolutely correct and very well stated!

The primary goal of abstraction, in terms of programming language and method design, is all about achieving a level of development that is as close to precise and unambiguous human language as possible.

The problems with achieving this in 3GL is that 3GLs don’t have proper separation of concerns in their design. This is why (e.g.,) most 3GLs have separate integer and real types; the machine limitations for processing integer and real numbers have imposed an artificial requirement for splitting the numeric type. The same goes for worrying about the memory size of data containers (e.g., byte, short, long, …) at the application level. In 3GLs, you can’t abstract away the machine limitations without introducing a layer of code that adds more processing and data usage burden.

I agree with Aitor. In our eagerness to focus on abstractions in the static domain, we often forget about contraints in the dynamic behavioral domain and abstract ‘time’ to obliviation. Real world software needs to provide results within certain timing expectations.

At Philips, i helped sponsor the creation of an interface definition language to specify and check behavorial and temporal constraints:

https://bits-chips.nl/artikel/comma-interfaces-open-the-door-to-reliable-high-tech-systems/

I was investigating the dichotomy algorithm/models from the early ‘80, starting from Simula to OOP thanks also to the visionary A. Kay.

Now we know the same “dialog” happen in our mind between abstractions, neural network patterns, language, and logic.

We are in a period of convergences

Low-code development can be extended to Modelling as Programming (MaP) or Models as a Program (MaaP) since the Modelling to Program (M2P) already high-lighted the path (see CCIS 1064 and 1401 (Springer)). It would be true fifth generation programming that starts with models and then uses models as source code for a program beside of being useful for program specification.

It is similar to second and third generation programming where programmers are writing programs in a high-level language and rely on compilers that translate these programs to machine code. We propose to use models instead of programs and envision that models can be translated to machine code in a similar way.

Models will thus become {\sl executable} while being as {\sl precise} and {\sl accurate} as appropriate for the given problem case, {\sl explainable} and {\sl understandable} to developers and users within their tasks and focus, {\sl changeable} and {\sl adaptable} at different layers, {\sl validatable} and {\sl verifiable}, and {\sl maintainable}.